Tourism is one of the pillars of the Sustainable Blue Economy and plays a key role in the preservation of a healthy ocean, our well-being and economic growth.

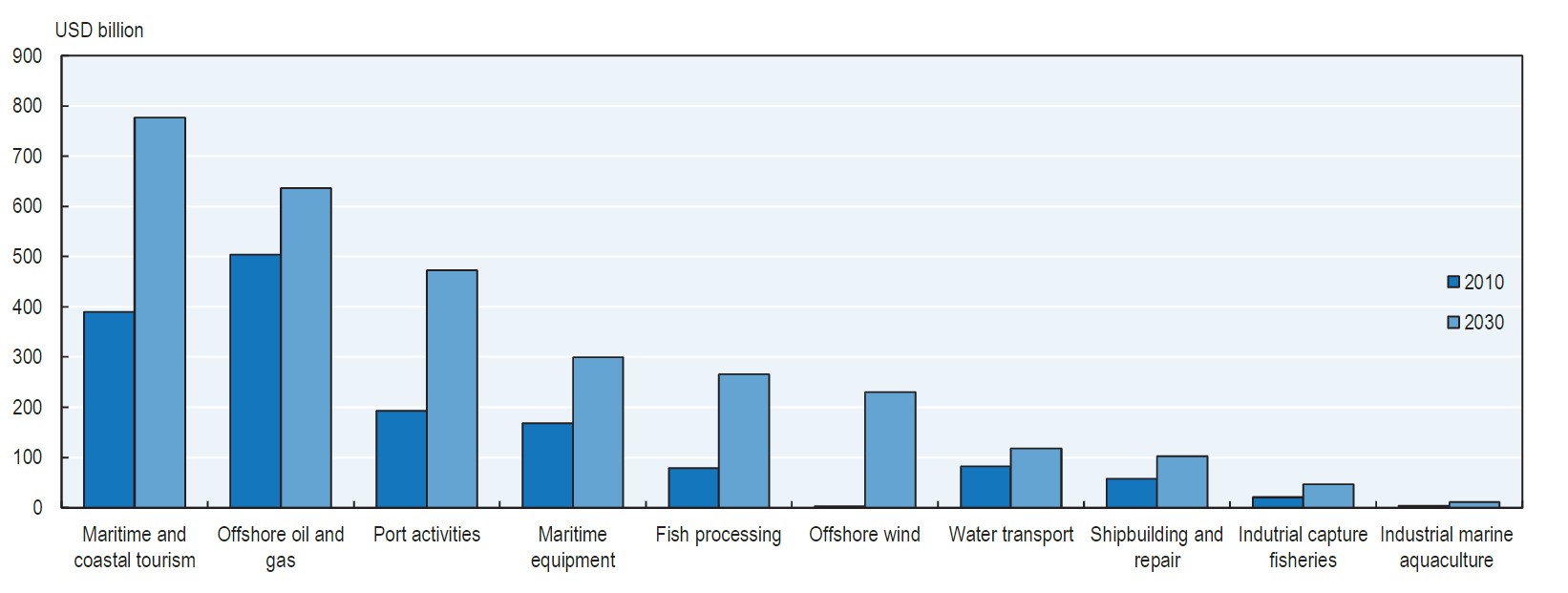

Around half of tourists chose coastal destinations for vacations in 2019. Prior to COVID-19, tourism accounted for 10.4 percent of global gross domestic product and 10 percent of all jobs across the world. Unsurprisingly, coastal and marine tourism was expected to result in the highest value add of all blue economy sectors in terms of jobs and value added[1] (Figure 1). Currently, the tourism sector has started its recovery with tourism numbers expected to return to 2019 levels by 2023[2].

Figure 1. Ocean-based industries’ value added was expected to double by 2030, with the tourism sector representing the highest value add.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), The Ocean Economy to 2030, 2016.

The pandemic has shown not only the economic relevance of the tourism sector but also its importance for biodiversity and marine conservation.

In many small island and coastal destinations, tourism revenues enable marine conservation efforts for natural assets that attract tourists, while addressing the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution highlighted by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)[3]. Funding examples for marine conservation include entrance fees, as for the Bunaken National Marine Park in Indonesia; nature or diving fees, as in Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles;; as well as voluntary contributions by tourists, as to the Galápagos Conservation Fund; or hotel taxes[4]. The decline in wildlife and marine tourism, a growing segment before COVID-19, has impacted funding for, among other things, biodiversity conservation, which is critical for many destinations. The ‘environmental management charge’ for the Great Barrier Reef, for instance, represented 14 percent of the Marine Park Authority’s budget in 2019[5]. In total, pre-COVID, the Great Barrier Reef contributed around 64,000 full-time jobs and more than AUS6.4 billion to the Australian economy annually[6]. In response to lost tourism revenues due to the pandemic, some governments have included financial measures in their COVID-19 recovery packages. The Australian government, for example, provides a waiver on the visitor charge for the reef until June 2023[7].

In the coming decade all blue economy sectors could offer unprecedented development and investment opportunities.

The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy estimates that sustainable ocean-based investments yield benefits at least five times greater than the costs, with minimum net returns of $8.2 trillion over 30 years[8]. According to the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles, sustainable blue economy finance ‘provides social and economic benefits for current and future generations; restores, protects and maintains diverse, productive and resilient ecosystems; and is based on clean technologies, renewable energy and circular material flows’.

While innovative financing mechanisms, such as blue bonds or public and development finance, are increasingly common, the blue economy receives less than 1 percent of official development assistance, and coastal and marine tourism receives a small fraction of this amount[9].

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14, ‘Life below Water’, currently receives the least investment and also the least amount of blended finance of all SDGs, though the cost of inaction is expected to range between $200 billion and $1 trillion annually by 2100[10]. Private investors show high interest in sustainable blue investments, but expertise is not yet developed, and little investment grade projects exist[11].

Lenders, investors, insurers, the public sector, multilateral banks and pension funds can use their leverage to provide financing to turn sustainable blue finance for the tourism sector from the pilot stage to large-scale investments at pace, enabling the ocean to continue providing significant social and economic benefits. Innovative financial instruments, such as sustainable blue debts, blended finance, equity or impact finance, and public-private partnerships can enable sustainable blue finance. The government of the Netherlands, for example, offers green investment funds which include tax benefits and reduced loan interest rates[12]. The investor community can also influence corporate policy for sustainable blue investments and actively seek to include the sustainable tourism sector. For example, Norges Bank, which manages one of the largest sovereign wealth funds[13], has established its ‘ocean sustainability expectations’ for companies, and in 2018 the World Bank’s support for the Seychelles’ US$15 million blue bond, the country’s first, led to the emergence of the blue bond market. While the bond amount in the Seychelles was small compared to a private sector bond, the leadership of multilateral banks is essential to pilot-test and scale-up financing by providing case studies and de-risking sustainable blue investments. . As Adonai Herrera-Martinez, Director at EBRD’s Environmental and Sustainability Department, highlighted: “Oceans and seas present vast opportunities for economic development and work creation. The unsustainable use of the marine environment is putting these prospects at risk as well as the livelihood and welfare of billions of people in coastal communities. There is a growing momentum towards a sustainable ocean economy, where Multinational Development Banks will play a role in providing finance and strategic guidance for policy makers. Therefore, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) should play a key role in bringing its private sector focus and Green Economy experience into this new Blue Economy paradigm. Sustainable coastal tourism is an essential piece for the restoration of the marine environment and the creation of economic opportunities. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it represented a quarter of the US$ 1.5 trillion Blue Economy, supporting more than 6.5 million jobs globally. The development of clear, simple and comprehensive guidelines to enhance sustainability aspects in tourism projects is essential for scaling up regenerative investments and ultimately achieving nature-positive impacts in marine ecosystems.”

The following five priority areas could facilitate the scale-up and acceleration of sustainable blue economy finance overall and in the coastal and marine tourism sector:

- A global ambition,a goal, or an aspiration as first step to increase and scale up sustainable blue economy action and finance . The Paris Climate Agreement is a leading example with the 1.5°C target. Except for climate change, in many areas a variety of goals and ambitions exist on national or regional level but not on a global level. However, there are positive signs, such as the recent commitment of governments at the UN Environment Assembly to develop a legally binding agreement to end plastics pollution[14], or at the UN Climate Conference in Glasgow (COP26), where the ocean was integrated into the Glasgow Pact and marine ecosystems were recognised as ‘carbon sinks’[15]. This recognition also highlights the importance and the intangible links of a green-blue world and economy, that is, that ocean and land, climate, biodiversity, and pollution need to be addressed jointly and policy ambitions interlinked. The UN Ocean Conference and the UN Climate Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh (COP27) this year are the next opportunities for nations to establish a united ambition for ocean health. COP27 can also define climate actions related to the sustainable blue economy and the tourism sector as part of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Clarification on the latter topic could increase investments significantly.

- A joint framework for an international understanding of what qualifies as sustainable blue economy and finance and its interlinkage to the green economy. Today, a variety of definitions, frameworks, and understandings of sustainable blue economy finance exist. The first foundational guiding framework in the ocean economy was provided by the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles, launched in 2018 for the finance sector and aligned to SDG 14 on Oceans by the European Commission, WWF, the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the European Investment Bank and hosted by the UNEP Finance Initiative (FI). Further guidance on the Principles was published by UNEP FI in 2021, outlining pathways and recommended actions across five key ocean sectors, including coastal and marine tourism[16]. On a regional level, the EU taxonomy will provide a classification system to facilitate sustainable investments to implement the European Green Deal, including investment related to a sustainable blue economy and tourism[17]. The next step should be to focus on collaboration to establish a joint understanding of sustainable blue economy and finance, and the intangible linkage to the green economy, an effort in which governments, multilateral banks and non-governmental organisations, in cooperation with the private sector, will play an essential role.

- Better and updated joint methodologies, data and benchmarks to increase sustainable blue-green finance in the tourism sector. For sustainable blue finance in the tourism sector, there is a lack of robust, comparable data, combined with a need for joint indicators that the finance sector can use for projects, such as the Green Bonds Principles[18]. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions accounting is one of the few measurement methodologies which is widely used and relatively advanced in terms of data clarity and transparency. However, for most environmental topics, a variety of indicators, data and measurements are used with little transparency on methodologies and consistency of measurement. Specifically for the tourism sector, research on international data and benchmarks is insufficient, and even the latest international benchmarks can date back several years. In addition, with increasing numbers of data providers and greater amounts of data and publicly available information, a recent study found that the disagreements among environment, social and governance (ESG) data providers are both significant and increasing[19]. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and WRI have thus for example developed a sustainable blue economy finance guidebook[20], including impact indicators, for the tourism sector which builds upon the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles and other main blue economy frameworks with the aim to pilot them on EBRD tourism investments. Environmental management and measurement tools with transparent and science-based measurement methodologies, such as the UNEP GHG Emissions and Resources Efficiency Data and Performance Monitoring tool, can also help to measure and compare better ‘blue’ and ‘green’ impacts of the tourism sector[21]. As for frameworks, cooperation across the public and private sector and civil society is pivotal to establishing a joint understanding of definitions, approaches, criteria, and indicators.

- Pilot testing and sharing of case studies by the public sector, bilateral agencies and multilateral development banks. A recent Credit Suisse study showcases investors’ keen interest in sustainable blue economy investment[22]. One-third of investors see the blue economy as one of the most important topics for 2030[23]. Pilot-phase blue finance mechanisms and products exist, such as BNP Paribas’s first Blue Economy Exchange–traded fund, the Chinese government’s blue bonds or the Blue Impact Bonds for Nature, a joint project between HSBC and The Nature Conservancy Australia. However, expertise is low and projects available, especially in the tourism sector, are often overall too small for financial viability and their risk-return profile is too high, whether this risk level is real or perceived due to missing project examples[24]. While coastal and marine tourism has been identified as the highest value added sector in the ocean economy, it is the least integrated sector in existing sustainable blue finance mechanisms, for reasons including its high number of small and medium sized business and its multifaceted, cross-sector nature compared to, say, fishing or shipping, as well as related missing data[25]. One of the few exceptions is Indonesia’s green sovereign green bond, the first in Asia, which also includes the tourism sector and blue economy elements. The public sector, multilateral development banks and bilateral development aid can help accelerate development and implementation of blue finance in the tourism sector by piloting and supporting financing and sustainable tourism projects. Public or public-private pilot projects can serve as a basis for finance institutions worldwide to build and scale-up their own finance mechanisms. EBRD, also a signatory of the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles, has for example decided to leverage its strong track record in protecting aquatic ecosystems across its countries of operation, which include some of the ocean’s most pressured areas, including the Aral Sea, one of the largest human-made environmental catastrophes in history. In particular, the Northern Dimension Environmental Partnership, which supports environmental remediation in the Baltic and Barents Seas to improve the health of the marine environment and fight eutrophication, is a replicable landmark for other marine ecosystems such as the Mediterranean, Red and Black Seas. Intensive oil and gas development in the Caspian and Black Seas have resulted in extensive air, water and land pollution, wildlife degradation, exhaustion of natural resources and desertification. Environmental degradation in the Mediterranean and on Atlantic coasts due to overfishing, untreated waste and real estate overdevelopment has brought major human and environmental threats. EBRD has thus also joined the Clean Oceans Initiative, the largest of its kind internationally. The initiative, which funds projects aimed at reducing plastic pollution at sea, raised its target to €4 billion of financing by the end of 2025, instead of the €2 billion initially expected to be reached by 2023[26].

- Capacity building of all stakeholders and further engagement of the private sector. While the blue economy concept and projects are not new per se, they have only recently begun to receive greater attention. The public sector will thus play a crucial role in advancing investments at the beginning. Development aid finance projects can, for example, help build capacity and integrate the sustainable blue economy into banks’ finance criteria or hotels’ investments. According to Joumana Asso, managing director of Clima Capital Partners, ‘By integrating blue economy tourism finance criteria as part of a concessional green finance package for national banks or as part of public-private partnerships, combined with capacity building and accompanying banks locally, blue economy projects can be created. At the same time, trust in sustainable blue finance investments will be increased and the investment risks reduced over time.’ Asso’s team is examining a potential blue economy, sustainable tourism–dedicated blended finance vehicle for Sri Lanka. This includes investment eligibility criteria for priority sectors, technologies and Sri Lanka’s geographical location as part of a larger framework considering national policies and NDCs for investments. Throughout the process, from conceptualising frameworks and indicators to establishing sustainable blue finance mechanisms, the private sector should be actively engaged for input and feedback. The more fully the private sector is included from the beginning, the more quickly sustainable blue finance mechanisms and products can be taken up.

While joint frameworks and comparable data are currently under development, the tourism sector can begin building capacity and implementing sustainable blue economy finance projects now. Large-scale investors from the public and private sectors have a key role to play in engaging with companies, start-ups, project developers, civil society and destinations to enable innovate blue-green finance mechanisms in the tourism sector at scale and pace.

—–

[1] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), The Ocean Economy to 2030, 2016, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/the-ocean-economy-in-2030_9789264251724-en#page1.

[2] https://www.reuters.com/world/the-great-reboot/global-tourism-recover-pandemic-by-2023-post-10-year-growth-spurt-2022-04-21/

[3] Tourism4 SDGs, “Secretary-General’s Policy Brief on Tourism and COVID-19: Key Messages,” August 2020, https://tourism4sdgs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Key-Messages-for-Tourism-and-COVID-19-Policy-Brief_-EN.pdf.

[4] Indians in Indonesia, “Bunaken National Marine Park: Details and Facts,” https://indiansinindonesia.org/bunaken-national-marine-park-details-and-facts/; Bonaire National Marine Park, “Stinapa Bonaire Presents: Rules and Regulations,” https://stinapabonaire.org/bonaire-national/; ;Galapagos Conservation Trust, home page, https://galapagosconservation.org.uk/.

[5] Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), Annual Report 2018–19, https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/3527.

[6] Great Barrier Reef Foundation, “The Value,” https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/the-value.

[7] GBRMPA, “Environmental Management Charge,” https://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/access-and-use/environmental-management-charge.

[8] M. Konar and H. Ding, A Sustainable Ocean Economy for 2050: Approximating Its Benefits and Costs, Secretariat of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2020), https://oceanpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Ocean-Panel_Economic-Analysis_FINAL.pdf.

[9] OECD, “Development Co-operation for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, 2021,” June 2021, https://www.oecd.org/ocean/topics/developing-countries-and-the-ocean-economy/development-co-operation-sustainable-ocean-economy-2019.pdf.

[10] U.R. Sumaila et al., “Financing a Sustainable Ocean Economy,” Nature Communications 12 (2021): 3259, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-23168-y.

[11] Credit Suisse, “Investors and the Blue Economy” https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/microsite-ux/docs/2021/decarbonizingyourportfolio/investors-and-the-blue-economy-en.pdf

[12] Business.gov.nl, “Green Projects Scheme,” https://business.gov.nl/subsidy/green-projects-scheme/,

[13] Norges Bank Investment Management, “Expectations towards Companies: Ocean Sustainability,” https://www.nbim.no/contentassets/17ed97a1a9f845ad8e847a51bc4b8141/nbim_expectations_oceans.pdf

[14] UN Environment Assembly of UNEP, “End Plastic Pollution: Towards an International Legally Binding Instrument,” 2 March 2022, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/38522/k2200647_-_unep-ea-5-l-23-rev-1_-_advance.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[15] UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, “Glasgow Climate Pact,” Decision -/CP.26, advance unedited version, November 2021, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cop26_auv_2f_cover_decision.pdf.

[16] UNEP, “Turning the Tide: How to Finance a Sustainable Ocean Recovery,” March 2021, https://www.unepfi.org/publications/turning-the-tide/.

[17] European Commission, “EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities,” https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en.

[18] International Capital Markets Association, Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds, June 2021, https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks/green-bond-principles-gbp/.

[19] S. Kotsantonis and G. Serafeim, “Four Things No One Will Tell You about ESG Data,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 31, no. 2 (Spring 2019): 50–58.

[20] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Blue Economy Finance Guidebook, 2022.

[21] One planet, “Resource Efficiency Data and Performance Monitoring Tool,” 5 November 2021, https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/knowledge-centre/resources/resource-efficiency-data-and-performance-monitoring-tool-0.

[22] Credit Suisse, “Investors and the Blue Economy,” 2020, https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/microsite-ux/docs/2021/decarbonizingyourportfolio/investors-and-the-blue-economy-en.pdf.

[23] Credit Suisse, “Investors and the Blue Economy.”

[24] UNEP, “Sustainable Blue Finance.”

[25] UNEP, “Sustainable Blue Finance.”

[26] European Investment Bank, “The Clean Oceans Initiative Doubles Its Commitment to Provide €4 Billion by 2025 to Protect the Oceans and Welcomes EBRD as New Member,” 11 February 2022, https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2022-092-the-clean-oceans-initiative-doubles-its-commitment-to-provide-eur4-billion-by-2025-to-protect-the-oceans-and-welcomes-ebrd-as-new-member.

Previous

Previous