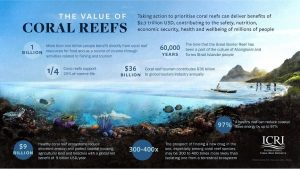

I’m a coral farmer, and my job shouldn’t exist. Growing coral to revitalise dying reefs is not an existence anyone should dream for. This single ecosystem, which covers less than 1 percent of the seafloor, sustains 25 percent of marine life[1]. Yet the reality we face is stark and fresh solutions are needed: half of the world’s coral reefs are dead and over 90 percent are on track to die by mid-century. This is not just an ecological tragedy but also a socioeconomic catastrophe, as coral reefs alone generate $2.7 trillion annually while supporting the livelihoods of up to 1 billion people[2]. 55 percent of global GDP depends on healthy ecosystems and 80 percent of all tourism occurs in coastal areas[3]. As one example among many of value at risk, how will tropical marine tourism be viable if guests no longer are drawn to destinations by the magic of coral reefs? We must urgently act to protect the ecosystems that support us all. By kickstarting a restoration economy, we can solve some of society’s most pressing challenges while creating a transformative model for nature-positive regenerative tourism and community-centric development.

In the 2020 “Trends and Statistics” report of the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST), Executive Director Dr. Gregory Miller noted, “As travel resumes post-COVID, we must have significant, enduring change toward quality over quantity tourism (value over volume). It is the quality of visitation, not the quantity of visitors that countries and destinations need to seek, and measure, with an individual and societal commitment to a responsible recovery.” In that same report, CREST states that “our beloved industry was on a path of self-destruction for decades, valuing profits at the expense of people, planet, and purpose. Sustainable tourism provides an economic incentive for destinations to avoid extraction-based economies, providing employment while decreasing carbon-intensive practices such as mining, deforestation, and slash and burn agriculture. Crisis breeds innovation, and destination communities and businesses must not let this opportunity go to waste.”[4]

I am a social entrepreneur, serving as the Co-Founder and Chief Reef Officer of Coral Vita, a mission-driven company that grows climate change–resilient coral up to 50 times faster to restore dying reefs. Integrating these novel methods pioneered by our original advisors into a high-tech land-based coral farming model, our work takes a different angle than traditional conservation initiatives in that we are a for-profit for-good enterprise. Rooted in our team’s lifelong love for nature, we recognised that unfortunately environmental arguments alone aren’t driving sufficient action to protect and revitalise ecosystems. Given the immense value coral reefs provide and what’s at stake with their loss, Coral Vita was created to help inject critically needed capital to scale restoration through a financially sustainable business model, rather than relying on disparate grants and donations. By selling restoration as a service to reef-dependent customers like resorts, developers, governments, insurers and more; using our farms as ecotourism attractions; and tapping into emerging conservation-financing mechanisms, we can (in partnership with other reef stakeholders) ultimately grow millions and billions of diverse, resilient and affordable corals. And given that as of 2018 “only 1/100th of 1% of climate finance was going to coral reefs,” profound change is rapidly needed[5].

I didn’t imagine I’d be an entrepreneur or a coral farmer, given that my academic and professional experiences were in environmental policymaking and non-profits. But when considering the impacts of rapid ecosystem loss and the urgent need for solutions, it became clear that, within the realities of our global economy, reimagining development systems could shift how we value and protect nature. Coastal tourism is inextricably linked with ocean health. As CREST pointed out, necessity creates opportunity. I believe the lessons and opportunities from coral restoration and nature-positive tourism are applicable globally to everything from mangrove forests to seagrass meadows to oyster reefs, and I hope that readers can visualise this world of opportunities. It’s also essential to acknowledge that while we must catalyse and seize these opportunities, the best thing for ecosystems’ health is and will always be for our leaders to stop killing them. As we wait for them to live up to their duties, we can get to work.

Among the many lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us, the one that sticks with me the most is that if we give nature a break, it can recover (though as also illustrated by lockdowns, some people took advantage of reduced environmental protection enforcements to illegally deforest, poach or mine). For example, beach closures in Florida correlated with a 39 percent increase in nesting success for endangered loggerhead turtles[6]. Nature can recover more effectively and rapidly with help from the appropriate types of restoration interventions. Roadmaps for protecting coral reefs and rebuilding marine life populations have already been created[7]. The natural world is incredibly resilient, and that’s something we should take inspiration from. But through society’s actions, we continue pushing it beyond its breaking point. We can see this in the mere fact that the field of coral restoration exists. We live at a time when entrepreneurs, community leaders, scientists, technologists, financiers and policymakers are being forced to consider how we can regrow ecosystems. That’s frankly absurd. But since we now must, let’s harness our collective resources and skills to start reversing the damage done and make environmental interventions the right way: funding and rebuilding on behalf of nature, biodiversity and the people whose lives depend on them.

I live on the island of Grand Bahama, where Coral Vita operates its first coral farm. As we grow coral to restore reefs and fulfil restoration contracts, the farm also operates as both an education and workforce development centre for local communities, as well as an ecotourism attraction in its own right. Visiting guests can pay to experience the interactive facility, as well as fund restoration in-person or online through our adopt-a-coral program. There are examples of organisations around the world that also give tourists the opportunity to plant corals onto reefs while snorkelling or scuba diving, a new take on restorative nature-based tourism. And the ecosystem value and experiences aren’t limited to coral reefs. In addition to swimming through them, one of the more popular tourist activities here (and many more places) is kayaking through mangrove forests. The still waters, mesmerising web of mangrove roots and myriad biodiversity on display underwater and in the air is a huge draw for places like Lucayan National Park or Thrift Harbor. It’s already a no-brainer that we should protect these forests. Especially when you consider they do everything from providing critical habitat for biologically and economically important marine species (which whether through migration or the food chain can even impact deep-sea fishing tourism) to sequestering up to 10 times more carbon dioxide per hectare than terrestrial forests. And like coral reefs, mangroves from India to Vietnam to Mexico can save lives and protect property by reducing wave energy, providing flood-defence benefits of over $65 billion annually[8]. It’s why insurance titans like Swiss Re, Willis Towers and AXA Watson are developing policies to incentivise mangrove and coral restoration.

I witnessed nature’s defences firsthand in 2019 when Grand Bahama and Abaco were struck by Hurricane Dorian, the strongest storm to hit the Bahamas in recorded history. Sustained winds of over 180 miles per hour battered the islands for nearly two days, together with a storm surge that reached 23 feet in some places (the coral farm was hit by a 17-foot wall of water). In the following months, our team engaged in rescue-and relief-efforts, particularly in East Grand Bahama. And it was there we learned how truly important mangroves are. In the settlement of Sweetings Cay, every person stayed put to weather Dorian. Despite receiving the eye of the storm and experiencing wind shifts from three different directions, there were no fatalities. When we asked people how they had survived, person after person pointed to the mangroves surrounding Sweetings Cay, sharing stories of how the trees slowed down the surge enough for residents to get to neighbours’ houses or higher ground. In the nearby settlement of Mclean’s Town, most mangroves had been removed in years past, and the death toll was heartbreaking. Unfortunately, the protection afforded by mangroves may not exist here when the next storms roll in, because the sheer power of Dorian destroyed over 70 percent of Grand Bahama’s and over 40 percent of Abaco’s mangrove forest according to the Bahamas National Trust.

What if we not only protected the ecosystems that protect us, power tourism economies and enable families to pay the bills but also created entire new experiential opportunities for tourists to help fund restoration?

Community-led mangrove restoration projects like ones here by Waterkeepers Bahamas, EarthCare and the Blue Action Lab (focused on forests devastated by Dorian) received seed funding in 2021 from international development agencies and initiatives like the Bahamas Protected Areas Fund[9]. But for a small fee, these efforts can be amplified and sustained by visitors who pay for the experience of planting mangroves. Tied in with local workforce development, supplemental income can be generated for, say, taxi drivers or tour operators who received certified training for building these nature-based tourism activities into their offerings. As part of Coral Vita’s contribution, we are hosting the mangrove nursery at our Freeport farm, and in the summer of 2022 ‘Mangrove Mania’ is launching to catalyse locals to form teams to learn why mangroves matter, collect mangroves for restoration and even win cash prizes for the teams that have the most impact. Creating a new activity for tourists and locals alike through ecosystem restoration that enhances valuable yet threatened ecosystem attractions (while providing a range of additional benefits like coastal protection and fisheries) is a slam dunk. Yet the lack of accountability demonstrated by our political, industrial and media leaders as well as ourselves as individuals is preventing us from acting collectively to solve the climate crisis, threatening to waste our opportunity to meet this moment and come together to help the most vulnerable among us, from frontline communities to biodiverse ecosystems.

It doesn’t have to be this way. One of the most frequently deployed arguments against acting in the interest of public and planetary health is that doing so poses a threat to economic prosperity. In reality, it is only a threat to entrenched and narrow interests and systems. For the rest of us, sustainability is a pathway to shared prosperity and security.

A report by the Future of Nature and Business outlined a blueprint to emerge from the pandemic with a ‘nature-positive’ economy that generates up to $10.1 trillion annually and creates 395 million jobs by 2030, while the World Resources Institute found that $5 in environmental, health and economic benefits are generated for every $1 invested in key ocean actions[10],[11]. If we are going to build an economy that serves people and the planet, we need to invest in sustainable infrastructure and long-term policies to address existential threats, systemic injustice and structural inequality.

In other words, socially responsible spending to realign tourism to become nature-positive is a no-brainer, as is socially responsibility for individuals and nations around the world. Empowering a restoration economy can revitalise threatened ecosystems and the benefits they provide while creating localised jobs and mitigating growing threats from the climate crisis. Clearly, we should be investing in our joint well-being, especially when it will yield such incredible dividends for society and the planet that sustains us all. Just as it is in our collective interest to rally and support our neighbours and country by making those small, yet necessary, sacrifices that we know work. We’re all in this together, and the ability to make a difference—whether by respecting trained scientists or demanding that our leaders effectively act in our shared interest—is in all of our hands. Lives hang in the balance. Failure is not an option. How will you rise to this challenge?

—–

[1] O. Hoegh-Guldberg, E.S. Poloczanska, W. Skirving and S. Dove, “Coral Reef Ecosystems under Climate Change and Ocean Acidification,” Frontiers in Marine Science, 29 May 2017, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00158. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2017.00158/full

[2] F. Staub, E. Corcoran and J. Greenlee, “Five A’s of the Coral Reef Indicators,” International Institute for Sustainable Development, SDG Knowledge Hub, 12 May 2021, https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/guest-articles/five-as-of-the-coral-reef-indicators/#:~:text=A%20recent%20estimate%20indicates%20coral,%2Dfishing%2C%20and%20destructive%20fishing.

[3] International Union for Conservation of Nature, “Nature-Based Recovery,” IUCN Issues Brief, https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/nature-based-recovery; WWF, “Blue Planet: Coasts,” http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/oceans/coasts/

[4] Center for Responsible Travel (CREST), “The Case for Responsible Travel: Trends & Statistics 2020,” September 2020, https://30ghywahyur3pzyoi3qg4r9c-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/213/2021/03/trends-and-statistics-2020.pdf.

[5] C. Cheney, “Can This New Fund Save Coral Reefs before It’s Too Late?,’ Devex, 11 November 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/can-this-new-fund-save-coral-reefs-before-it-s-too-late-101905.

[6] For some of the good, and some of the harmful, consequences of the abrupt change in human behaviour in 2020, see B. Owens and H. Magazine, “Nature Isn’t Really Healing,” Atlantic, 30 May 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2021/05/pandemic-lockdowns-nature-wildilfe/619054/.

[7] International Coral Reefs Society, “Rebuilding Coral Reefs: A Decadal Grand Challenge,” July 2021, http://coralreefs.org/publications/rebuilding_coral_reefs; C.M. Duarte, S. Agusti, E. Barbier, G.L. Britten, J.C. Castilla, J.-P. Gattuso, R.W. Fulweiler et al., “Rebuilding Marine Life,” Nature 580, nos. 39–51 (2020), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2146-7.

[8] P. Menéndez, I.J. Losada. S. Torres-Ortega, S. Narayan and M.W. Beck, “The Global Flood Protection Benefits of Mangroves,” Scientific Reports 10, no. 4404 (2020), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-61136-6.

[9] Waterkeepers Bahamas, “Mangrove Planting,” Facebook, 1 April 2022, https://www.facebook.com/242Waterkeepers/videos/mangrove-planting/2177868489031089/.

[10] World Economic Forum, New Nature Economy Report II: The Future of Nature and Business, 14 July 2020, https://www.weforum.org/reports/new-nature-economy-report-ii-the-future-of-nature-and-business

[11] M. Konar and H. Ding, A Sustainable Ocean Economy for 2050: Approximating Its Benefits and Costs, High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2020). https://www.oceanpanel.org/economicanalysis

Previous

Previous