The untapped potential of private sector involvement in marine governance

In 2016, nations around the world committed to a 30×30 target—to ensure that 30 percent of the world’s ocean (and its land area) is protected and managed effectively and equitably by 2030[1]. In the marine realm, this has meant scaling up the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) around the world. These are largely developed and managed by governments and state entities, and while this form of governance can be politically and legally robust, it is often challenged by a lack of financing (with conflicting government priorities), inadequate staffing and on-site management, and a lack of capacity to manage sometimes vast oceanic areas effectively[2]. This has led to a plethora of ‘paper parks’, meaning they exist on paper but without management actions or increased biodiversity protection on the water[3].

Other forms of MPA governance have gained recognition in recent years. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines additional categories of governance as community-led (by Indigenous peoples and local communities), private governance (by private sector entities) and shared governance (through a combination of the above or transboundary)[4].

Among these categories, IUCN defines a privately protected area (PPA) as a protected area under private governance, that is, ‘by individuals and groups of individuals; non-governmental organisations; corporations, including commercial companies and small companies established to manage groups of PPAs; for-profit owners such as ecotourism companies; research entities such as universities and field stations; or religious entities’[5].

In terrestrial conservation, a wide range of PPAs exist and have advanced considerably in recent years, while in the marine sector relatively few are formally recognised. Expectations of the private sector’s involvement in marine conservation has remained largely limited to philanthropic funding or corporate social responsibility contributions. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that the private sector can go far beyond providing supportive funds for a site; under the right circumstances, it can offer holistic, cost-effective and full-package management services for MPAs[6].

An untapped opportunity

The private sector’s interest in supporting marine governance is not new, particularly the tourism sector. Since the 1990s there have been discussions about the potential for ‘entrepreneurial MPAs’, ‘marine conservation agreements’, dive tourism–led conservation areas, and ‘hotel managed marine reserves’[7]. But few of these approaches have gained traction or recognition in the conservation community, with criticism often levelled at private sector involvement for being inequitable or for including exclusionary principles (for example, tourism businesses creating self-declared set-asides for dive tourists, or beach access areas excluding local stakeholders and/or lacking legal recognition). Certainly these challenges have existed, and not all private sector actors implementing such efforts have had biodiversity conservation and collaboration at their core. But this distrust of private sector actors has overshadowed the considerable achievements that are possible when appropriate conditions apply.

Two of the best-known examples of successful marine privately protected areas (M-PPAs) are Chumbe Island in Zanzibar, Tanzania, and Misool Marine Reserve in Indonesia. Both of these M-PPAs are formally recognised protected areas, and both are led by ecotourism businesses.

Chumbe Island Coral Park

Uninhabited Chumbe Island (Figure 1) was identified as a marine biodiversity hotspot in 1991, and a private company, Chumbe Island Coral Park Ltd. (CHICOP), was established to lobby for the island’s protection. Through CHICOP’s efforts the Chumbe Island MPA was legally gazetted in 1994, including a no-take coral reef sanctuary and fully protected forest reserve on land.

Figure 1. Chumbe Island

Source: Chumbe Island Coral Park Ltd.

Management agreements were signed between CHICOP and the government of Zanzibar for CHICOP to fully finance and manage the site, making it world’s first M-PPA. A small area of the island was leased to CHICOP for the establishment of an ecolodge to fully fund operations as a not-for-profit entity, with all revenue generated from visitors to the island funding conservation management and an extensive education program for local schools, communities and wider stakeholders. This also made Chumbe the world’s first financially self-sustaining MPA.

The ecolodge was developed with state-of-the-art eco-architecture and technology to ensure zero impact on the environment; and outreach and employment opportunities were targeted to nearby communities from the outset, with job creation extending to support wider enterprise development locally. The management agreements and separate development lease are fixed-term renewable.

Since the island became an M-PPA, peer reviewed studies have shown that fish biomass in the no-take reef sanctuary has increased by 750 percent, with the spillover effect supporting sustainable fisheries and food security many kilometres from Chumbe’s borders, with live hard coral cover reaching 80 percent coverage in the protected area. The project has also provided education services to more than 13,000 schoolchildren and community members and continues to run a range of community support and enterprise development initiatives locally.

Misool Marine Reserve

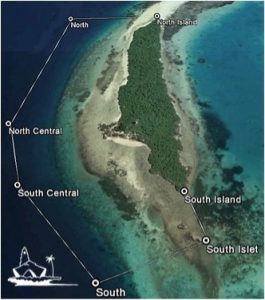

Located in Raja Ampat (Papua, Indonesia), Misool Eco Resort (MER), a private company, began operations in 2005 when it entered into a lease agreement with local traditional owners to build an ecolodge and establish a no-take marine reserve in the area to protect the region’s marine biodiversity (Figure 2). Concurrently, the government of Indonesia was establishing an MPA at the site (with overlapping boundaries, the MPA covering a larger area), and thus the MER no-take reserve became embedded in the legally gazetted MPA as one of the MPA’s no-take zones (NTZs).

Figure 2. Misool Marine Reserve

Source: Misool Foundation (Baseftin).

To manage the area, MER established the Misool Foundation as a separate conservation management entity, and over time the areas leased for conservation management expanded to cover a total of 1,220 square kilometres, including two large NTZs bridged by a restricted gear corridor. The foundation employs, trains and empowers local community members to manage the area through regular patrols and a range of conservation research and policy initiatives.

The lease arrangement with these communities includes a financial payment (fixed term, renewable), and the provision of a range of support services. This includes a community education program (support for local school operations and scholarships for advanced education) and a community recycling service. MER and the foundation also provide essential employment and training opportunities to these remote communities.

Since the site became an M-PPA, peer reviewed studies have shown that fish biomass in the NTZs has increased by 250 percent, and there are approximately 25 times more sharks within the reserve than directly outside of the protected areas. Oceanic manta sightings also increased 25-fold between 2010 and 2016.

In both Chumbe and Misool, the drive to protect and sustainably manage the marine ecosystem, and engage and support local communities, was at the core of their business models. The projects showcase replicable innovation in sustainable ocean management and have catalysed a growing recognition that M-PPAs can provide a credible alternative governance approach to conservation area management.

Unlike under-resourced state-managed MPAs, M-PPAs can generate the means to finance and manage the site independently, they can be appropriately staffed with a strong on-the-ground presence, they can create job opportunities and support local livelihoods, and they have a vested business interest in the long-term health of the marine environment upon which their operations depend.

Replicating and scaling this approach requires important conditions to be in place, which we detail below. The international conservation community has an important role to play in promoting these conditions to incentivise a shift to sustainable coastal and marine management through wider private sector engagement.

Willingness to engage in public-private partnerships—Greater acknowledgement is needed of the role the private sector (particularly tourism businesses) can play in global ocean governance, and engagement with this sector must be strengthened. In nearly all M-PPAs established, some form of public-private partnership will be required in order for the site to be formally recognised and legally endorsed, whether through management agreements (as in the case of Chumbe), or through tiered management and traditional leasing (as in the case of Misool). Governments need policy frameworks and mechanisms to enable this, and the international conservation community can provide support in terms of guidance and endorsement.

Security of tenure—Establishing an M-PPA requires long-term planning and investment, which in turn requires security of tenure. For example, some M-PPAs may be based on leasehold arrangements or other fixed-term agreements; and while some term for review should be established to ensure all parties are achieving their commitments, the tenurial arrangement needs to be possible for the very long term to ensure that the M-PPA remains protected and effectively managed into the future.

Investment incentives—Private sector investors in M-PPAs will be taking on triple-bottom-line[8] commitments in their financing that generally go far beyond regular business investor commitments. This includes investment in outreach and awareness-raising programs about the mutual benefits of marine conservation and NTZs for fishers, schools and wider communities, including political leaders, as a precondition for winning support and building successful local partnerships. Providing incentives can help encourage these social entrepreneurs, whether they be tax incentives or operational incentives that help reduce non-commercial costs linked to key management achievements.

Transparent triple-bottom-line management goals, targets and indicators—Private sector actors need to be able to clearly demonstrate their business plans and mechanisms to deliver effective M-PPA management. This includes transparent management planning, with clear goals, targets and indicators related to the operations’ social objectives, conservation management objectives, and their business and financing objectives.

Clear engagement mechanisms and involvement of local communities—The success of any M-PPA will rely heavily on the effective engagement and involvement of local communities and stakeholders from the outset (as in the cases of Chumbe and Misool). To this end, any private sector endeavour to establish an M-PPA needs to be able to demonstrate the methods that will be used for this engagement. This may be through proactive job creation, livelihood support, education programs, involvement of local leaders as advisors to the project or other mechanisms to ensure local support for the initiative and involvement in it.

Clear adaptive management mechanisms for biodiversity conservation—An M-PPA needs to be able to deliver on its biodiversity conservation commitments. To this end, appropriately skilled technical staff and/or advisors need to be engaged and trained to ensure effective conservation management. This may include social scientists, biophysical scientists, outreach and educationalists. Management planning should demonstrate that effective adaptive management mechanisms are place to ensure the preservation of the sites’ ecology and biodiversity, and regular (ideally peer-reviewed) reporting mechanisms need to be in place.

The path ahead

In recent years the dialogue around M-PPAs has intensified. In 2016 IUCN called on member states to promote PPAs (both terrestrial and marine) to support ecosystem integrity (Resolution #036 WCC), and more recently the discourse around alternative governance frameworks has recognised ‘Other area-based Effective Conservation Measures’ (OECMs) as a mechanism to reflect wider marine conservation efforts under a range of governance typologies[9]. Sustainable financing for MPAs has become an increasingly targeted topic, resulting in increased recognition of the role social entrepreneurs and ‘impact investors’ must play in supporting marine governance[10]. Nonetheless this discourse remains largely confined to the international conservation community, with private sector representation being predominantly provided by large corporate foundations or investment entities.

M-PPAs are more likely to be established and operated by small to medium enterprises (SMEs), who have a direct vested interest and will maintain long-term on-the-ground presence at a site, yet these potential actors remain largely outside of discussions. Engaging these SMEs through international as well as nationally or regionally specific dialogue, through established PPA and tourism sector associations[11] and other platforms, will be important, as will providing more universal guidelines to governments, non-governmental organisations and potential M-PPA investors and operators (ideally developed collaboratively with private sector actors who have experience in the realities and operational imperatives of M-PPA governance).

As the world seeks to accelerate the establishment and effective management of marine biodiversity refuges, we can no longer keep the private sector at bay. All stakeholders need to be engaged if we are to achieve the 30×30 targets, and to conserve vital marine ecosystems and ocean productivity into the future.

—–

[1] International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), “Supporting Privately Protected Areas,” WCC 2016 Res 036, 2016, https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/46453.

[2] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Marine Protected Areas: Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276208-en.

[3] L. Coad, J.E.M. Watson, J. Geldmann, N.D. Burgess, F. Leverington, M. Hockings, K. Knights and M. Di Marco, “Widespread Shortfalls in Protected Area Resourcing Undermine Efforts to Conserve Biodiversity,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17, no. 5 (2019): 259–64; E. Di Minin and T. Toivonen, “Global Protected Area Expansion: Creating More than Paper Parks,” Bioscience 65, no. 7 (2015): 637–38; D.A. Gill, M.B. Mascia, G.N. Ahmadia, L. Glew, S.E. Lester, M. Barnes, I. Craigie et al., “Capacity Shortfalls Hinder the Performance of Marine Protected Areas Globally,” Nature 543, no. 7647 (2017): 665–69.

[4] N. Dudley, ed., Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 2008); P.J.S. Jones, R.H. Murray and O. Vestergaard, “Enabling Effective and Equitable Marine Protected Area: Guidance on Combining Governance Approaches,” UN Environment Programme, 2019.

[5] B.A. Mitchell, S. Stolton, J. Bezaury-Creel, H.C. Bingham, T.L. Cumming, N. Dudley, J.A. Fitzsimons et al., Guidelines for Privately Protected Areas, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series no. 29 (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 2018).

[6] IUCN, The Futures of Privately Protected Areas, 2015, https://www.iucn.org/content/futures-privately-protected-areas; IUCN, “Supporting Privately Protected Areas”; L. Nordlund, U. Kloiber, E. Carter and S. Riedmiller, “Chumbe Island Coral Park: Governance Analysis,” Marine Policy 41 (2013), doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.018.

[7] S. Colwell, “Entrepreneurial Marine Protected Areas: Small-Scale, Commercially Supported Coral Reef Protected Areas,” in Coral Reefs: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Management, 110–14 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 1997); J. Udelhoven, E. Carter and B. Gilmer, Marine Conservation Agreements: Feasibility Analysis in the Coral Triangle—Indonesia (Arlington, VA: The Nature Conservancy, 2010); J. De Groot and S. Bush, “The Potential for Dive Tourism Led Entrepreneurial Marine Protected Areas in Curacao,” Marine Policy 34 (2010): 1051–59, 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.03.004; C. Torres and N. Hanley, “Economic Valuation of Coastal and Marine Ecosystem Services in the 21st Century: An Overview from a Management Perspective,” DEA Working Paper no. 75 (2016), Universitat de les Illes Balears.

[8] In economics, the triple bottom line maintains that business operations benefit ‘three’ bottom lines—financial, social and environmental—as a measure of performance as businesses advance achievements for profit, people and the planet. J. Elkington, “Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development,” California Management Review 36, no. 2 (1994): 90–100; T. Hacking and P. Guthrie, “A Framework for Clarifying the Meaning of Triple Bottom-Line, Integrated, and Sustainability Assessment,” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 28 (2008): 73–89.

[9] OECMs are different from PPAs. OECMs are defined as “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation of biodiversity with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio–economic, and other locally relevant values” (CBD/COP/DEC/14/8–2018). Therefore, while OECMs are not legally protected areas (and may not have conservation as a primary reason for preservation), M-PPAs are formally and legally protected areas (and do have conservation as a primary reason for preservation).

[10] Impact investing seeks to generate financial returns while also creating a positive social or environmental impact. This can include socially responsible investment and environmental, social and governance investment. Beyond impact investing, philanthropic investing is also becoming a more accepted term to define the contribution of donor funds to social or environmental business entities with clear biodiversity conservation and social support targets.

[11] A number of national PPA associations and an international network exist. The Long Run (https://www.thelongrun.org/) is a non-profit organisation that aims to expand nature conservation by the private sector and within the tourism industry by offering sites certification as Global Ecosphere Retreats, a standard recognised by the Global Sustainable Tourism Council.

Previous

Previous