Co-author: Fernanda Rodak, Pacific Asia Travel Association, Project Coordinator—Sustainability & Social Responsibility

“When humans are faced with adversity, there is an opportunity to make change.”

—Prasad Kariyawasam[1]

The COVID-19 pandemic has painfully proven that tourism destinations must be resilient not only to recover from the current crisis but, also and more important, to better withstand future adversities and ‘bounce forward’ from crises that will surely come[2]. This article, therefore, presents a pathway for coastal and marine destinations to build resilience and progress towards sustainable tourism development.

Coastal and marine destinations are key stakeholders in sustainable tourism development, as upwards of 80 percent of all tourism takes place in coastal areas. While this creates economic benefits, the popularity of coastal destinations among tourists puts pressure on local infrastructure, communities and environments. In fact, some destinations report marine pollution increasing up to 40 percent at the peak of a tourist season[3]. Mismanagement at the local level of, for example, wastewater treatment or plastic waste has resulted in many Asian tourism hotspots losing their very reason for being: a pristine marine and coastal environment[4].

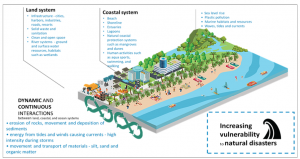

The interconnectedness of land, coastal and ocean subsystems is highly vulnerable to tourism development, and, as tourism grows, so do its potential negative impacts. Plastic pollution, for instance, from a socioeconomic perspective, leads to the devaluation of waterfront properties and decreased visual attractiveness[5]. This poses a serious threat particularly to destinations and countries where tourism is a major contributor to gross domestic product (GDP) and employment. The tourism industry needs a healthy ocean.

Contrary to what would be expected, however, the recently published Travel and Tourism Development Index highlights that many countries in the Asia Pacific region rank highly in natural resources but underperform in environmental sustainability[6]. If limited investment in environmental sustainability pushes development beyond a system’s carrying capacity, it will inevitably increase vulnerability to external threats, as seen in the diagram below, such as climate change and resulting sea level rise, as well as sudden shocks from natural disasters, conflicts and global pandemics.

Source: S.C. Sandhu, V. Kelkar and V. Sankaran, “Resilient Coastal Cities for Enhancing Tourism Economy: Integrated Planning Approaches,” Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Working Paper Series, no. 1043 (November 2019), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/541031/adbi-wp1043.pdf.

How can a coastal destination prepare for such adversities?

Post-COVID consumer trends show an increased interest in sustainable tourism and nature-based activities. Nevertheless, for coastal and marine tourism to drive economic recovery from the pandemic without further damaging the marine ecosystem, there must be investment in proactive destination management approaches. A focus on sustainability efforts must increase significantly to ensure the protection of coastal communities and environments, yet these efforts are not sufficient. Years of progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, such as reforesting coastal mangroves or regenerating coral reefs, for example, could be lost in a single disaster or crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of the extent of a crisis’s impact. In the Asia Pacific, the tourism contribution to GDP dropped by 53.7 percent in 2020 compared to the previous year. Also, travel and tourism employment fell by 18.4 percent, a loss of 34.1 million jobs[7]. COVID-19, moreover, caused severe setbacks in the region’s fight against plastic waste and marine pollution. Over 25,000 metric tons of COVID-19 plastic waste have already leaked into the ocean, and Asia is responsible for much of this number[8]. Finally, protected areas, national parks and heritage sites across the world have struggled to continue their conservation efforts due to the lack of revenue and reduced staff resulting from COVID-19[9].

These examples show that destinations worldwide have suffered severe consequences due to a lack of adaptive capacity, resilience and preparedness for a crisis of this scale.

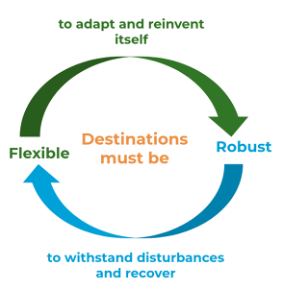

Sustainability, therefore, is not enough. Before a destination can be sustainable, it must first be resilient. Only when they are both sufficiently robust to withstand shocks and flexible enough to adapt to changes can destinations consider themselves resilient and be able to maintain their sustainability efforts[10].

Source: Authors

What does resilience entail for tourism destinations?

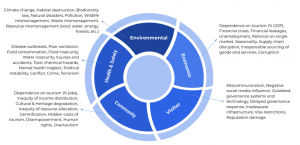

To begin developing resilience, the Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) compiled five resiliencies for tourism destinations: environmental, economic, visitor, community, and health and safety. Each has associated risks that, if not adequately addressed, can threaten the destination’s success and sustainability.

Environmental resilience refers to a destination’s preparedness to cope with natural shocks, take action against climate change, preserve wildlife and biodiversity, and adequately manage its natural resources, on which tourism is heavily dependent. Economic resilience, in contrast, involves having the financial means and stability to withstand crises, which is achieved, among other things, through economic diversification, strong local supply and demand, and adequate financial capacity. Visitor resilience concerns the safe and high-quality experience of travellers at the destination, an experience that should be supported by trustworthy infrastructure, services and communications. Community resilience refers to communities’ ability to retain the positive impacts of tourism without compromising their well-being, culture and heritage. And, lastly, health and safety resilience encompasses the capacities, infrastructure and services in place to protect residents and visitors from, for example, accidents, diseases, crime and terrorism.

The resiliencies are often counterintuitive and can present quandaries for destination managers who are often under-resourced and, therefore, under-prepared to have the correct mitigation systems, procedures and infrastructure in place to prevent a risk from becoming a crisis. Yet this is the starting point for all destinations.

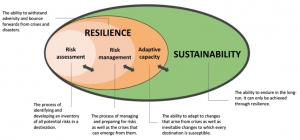

Next, tourism destinations require a pathway on their journey towards resilience. PATA defines tourism destination resilience (TDR) as both a process and an outcome that enables tourism destinations to withstand adversity and bounce forward from crises and disasters. To put this into practice, PATA provides a framework, outlined in the diagram below, that highlights the core components of resilience—risk assessment, risk management and adaptive capacity—and the relationship between resilience and sustainability.

While all aspects of the TDR framework are equally important, adaptive capacity is possibly the area in greatest need of attention. This term refers to the specific set of skills, tools and actions established by destinations to allow them to cope with change. These actions include, for instance, building financial, institutional and societal capacities in the destination; developing resilient and high-quality infrastructure and services; strengthening the local and regional supply and demand; and diversifying the tourism offer.

Looking at the first action, capacities can be best described as the combination of strengths, attributes and resources within an organisation, community or society to manage and reduce disaster risks and strengthen resilience[11]. While several capacities need to be identified and strengthened at the destination level, as identified by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction’s Making Cities Resilient[12], the three priorities are (1) developing financial mechanisms to support resilience activities; (2) strengthening the institutional capacities of governmental bodies, the private sector and industries as well as academic, professional and civil society organisations; and (3) increasing social cohesion and community participation for preparedness and successful risk management.

Resilient infrastructure and services constitute another key element for increasing a destination’s adaptive capacity, as it reduces the life-cycle cost of assets, the destination’s vulnerability to hazards and the community’s reliance on external services and facilities[13]. When infrastructure is resilient it is able to provide the services that users need during and after a natural shock. However, different infrastructure requires different preparation and coping mechanisms for different kinds of shocks. Destinations must therefore be able to assess and prepare for risks; provide proper financing and incentives for infrastructure planning; enforce regulations in construction codes; and follow through with appropriate operations, maintenance and post-incident responses[14].

The COVID-19 pandemic and previous crises that affected tourism destinations have proven that focusing on local and regional supply and demand is another important strategy for building resilience. From the supply side, it means prioritising local products, resources and services in tourism offerings to reduce reliance on international supply chains as well as economic leakages[15]. From the demand side, although international tourism often receives more attention due to its capacity to generate export revenues, domestic tourism can represent a much larger market in several countries. Destinations with higher shares of local and regional travel are likely to recover earlier and faster[16].

The last necessary strategy covered by TDR for increasing adaptive capacity in destinations is the diversification of the tourism offer. A diversified tourism portfolio reduces seasonality, mass tourism and overtourism; dependencies on tour operators of specific markets; and environmental, economic and social harms. This is because diversification of markets and products helps disperse tourism revenue to rural areas and communities, increases yield and occupancy, and is an important driver for innovation[17].

So how can a coastal destination succeed after COVID?

To meet the challenges of reopening and building a more resilient and sustainable tourism industry, PATA provides a public resource aiding in the rapid, robust and responsible renewal of the Asia Pacific travel and tourism industry, the Tourism Destination Resilience (TDR) project[18]. Besides the online resource, the programme also includes in-destination workshops with DMOs and other destination stakeholders, conducted in local languages.

To date, TDR workshops have taken place in destinations in the Philippines, Indonesia, Cambodia and Vietnam and prioritised high-level adaptive capacity needs such as the following:

- Integrated tourism planning—governance is a key in building resilience and sustainability of DMOs. Diversity of attractions and activities in each destination required specific knowledge and skills to manage within and between destinations.

- Capacity building—many current tourism department staff have limited experience with global best practices for destination management, hindering their ability to implement national policies. Research is not easily available, or the budget is very limited, which is why decision-making that goes into tourism development plans is not well-founded on data.

- Product development—local tour operators and accommodation providers struggle to innovate or create attractive tourism packages because of a lack of experience or knowledge in product development. Technical assistance for product capacity development training and business consultations are needed to create products’ target markets and ensure tighter alignment of the marketing value propositions with the actual tourist experience.

- Infrastructure development—in tourism destinations, the increased production of solid and liquid waste can be a major issue due to the absence of proper infrastructure to mitigate impacts. In many coastal areas, resorts rely mostly on the use of septic tanks to manage their sewage or hauling services, which do not guarantee proper disposal. Unsustainable practices in the disposal of solid waste can include burning, throwing it in water bodies including the ocean, and burying it underground. Some simply dispose of waste by the roadside. Often leachates percolate down to the aquifers, polluting underground water systems, rivers and [the ocean].

The destinations taking part in TDR can identify the adaptive capacities needed, but they may not have the means or resources to deliver the requisite governance, capacity or infrastructure to rapidly meet changes and close the gaps. This is where TDR can assist by providing the partnerships and collaboration for knowledge exchange, peer-to-peer learning, financial planning and capacity-building resources that can really benefit destinations.

TDR therefore aims to address the gap between destination management, resilience and sustainability. In the past, destination management was often a reactive process in response to crises, but it must now transition to a proactive, forward-looking and future-oriented approach. Destination management of coastal areas should be concerned with the future of tourism and adopt a coherent risk management process for TDR. As we have noted, coastal and marine tourism needs a healthy ocean—but a healthy ocean requires destination governance for resilience.

PATA will continue to provide the TDR programme to coastal and marine areas and will promote the requisite tools and resources across Asia and the Pacific. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the current global challenges, actions are urgently needed to strengthen the resilience of coastal and marine tourism destinations. PATA, with the TDR programme, is pleased to be taking part in that process.

The Tourism Destination Resilience project is implemented by PATA in cooperation with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

—–

[1] Quoted in H. Schafer and C. Fruman, “South Asia Unites to Double Down on Marine Plastics Pollution,” World Bank Blogs, 27 May 2021, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/south-asia-unites-double-down-marine-plastics-pollution.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “The Evidence Is Clear: The Time for Action Is Now. We Can Halve Emissions by 2030,” press release, 4 April 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease/.

[3] Global Tourism Plastics Initiative, “Tourism’s Plastic Pollution Problem,” One Planet, 2021, https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/programmes/sustainable-tourism/global-tourism-plastics-initiative/tourisms-plastic-pollution-problem.

[4] S.C. Sandhu, V. Kelkar and V. Sankaran, “Resilient Coastal Cities for Enhancing Tourism Economy: Integrated Planning Approaches,” Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Working Paper Series, no. 1043 (November 2019), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/541031/adbi-wp1043.pdf.

[5] Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA), Plastic Free Toolkit for Tour Operators, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f24290fd0d0910ecab2b02e/t/601d0015cbe7a12057dbde0d/1612513305647/PlasticFree-TourOperator-2021-Feb2.pdf.

[6] World Economic Forum, Travel and Tourism Development Index: Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future. Insight Report. May 2022. https://www.weforum.org/reports/travel-and-tourism-development-index-2021/in-full

[7] World Travel and Tourism Council, Travel and Tourism: Economic Impact 2021, https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/Global Economic Impact and Trends 2021.pdf?ver=2021-07-01-114957-177.

[8] Y. Peng, P. Wu, A.T. Schartup and Y. Zhang, “Plastic Waste Release Caused by COVID-19 and Its Fate in the Global Ocean,” PNAS, 8 November 2021, https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2111530118.

[9] International Union for Conservation of Nature, “COVID-19 Fallout Undermining Nature Conservation Efforts,” 11 March 2021, https://www.iucn.org/news/world-commission-protected-areas/202103/covid-19-fallout-undermining-nature-conservation-efforts-iucn-publication.

[10] S. Hartman, “Resilient Tourism Destinations? Governance Implications of Bringing Theories of Resilience and Adaptive Capacity to Tourism Practice,” in Destination Resilience: Challenges and Opportunities for Destination Management and Governance, edited by E. Innerhofer, M. Fontanari and H. Pechlaner (London: Routledge, 2022), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323119888_Resilient_Tourism_Destinations_Governance_implications_of_bringing_theories_of_resilience_and_adaptive_capacity_to_tourism_practice

[11] UN Environment Programme, Disaster Risk Management for Coastal Tourism Destinations Responding to Climate Change, 2008, https://www.preventionweb.net/files/13004_DTIx1048xPADisasterRiskManagementfo.PDF.

[12] UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, “The Ten Essentials for Making Cities Resilient,” 2017, https://mcr2030.undrr.org/ten-essentials-making-cities-resilient.

[13] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Building Resilience: New Strategies for Strengthening Infrastructure Resilience and Maintenance, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/infrastructure/Building-Infrastructure-Resilience-OECD-Report.pdf.

[14] S. Hallegatte, J. Rentschler and J. Rozenberg, Lifelines: The Resilient Infrastructure Opportunity (Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2019), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31805.

[15] J. Connell, “Blue Ocean Tourism in Asia and the Pacific: Trends and Directions before the Coronavirus Crisis,” ADBI Working Paper Series, no. 1204 (December 2020), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/661986/adbi-wp1204.pdf.

[16] World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), “Understanding Domestic Tourism and Seizing Its Opportunities,” UNWTO Briefing Note, September 2020,https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284422111.

[17] A.M. Benur and B. Bramwell, “Tourism Product Development and Product Diversification in Destinations,” Tourism Management 50 (October 2015): 213–24, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261517715000412.

[18] PATA, “Tourism Destination Resilience (TDR),” Crisis Resource Center, https://crc.pata.org/.

Previous

Previous